Estimate of Potential Economic Impact

Associated with “Aerotropolis” Legislation and an International

Freight Hub at Lambert-St. Louis International Airport (20/30)

Introduction

The Big Idea was never about two or three inbound cargo flights each week

from China. International air cargo is, however, where The Big Idea begins,

and the catalyst for St. Louis’ reemergence as a global center for

commerce and transportation.

St. Louis-based air cargo is the missing piece of a multi-modal infrastructure

system that today boasts enviable assets in highway, rail, and river transportation.

Only air cargo can deliver the speed-to-market essential for today’s

supply chains; which knit together from around the world components arriving

by varying modes of transport—all arriving at a preordained time

and place to be assembled into something more valuable than the sum of

their parts. Introducing and sustaining international air cargo service

in St. Louis will actually serve to stimulate and grow all other modes

of transport as well, taking full advantage of the region’s multi-modal

network.

The true vision of The Big Idea is about “re-internationalizing”

St. Louis as a vigorous cargo gateway; strengthening Lambert-St. Louis

International Airport through new landing fee revenues; and building a

more robust logistics cluster that invests hundreds of millions of dollars

in facilities and equipment, and employs thousands of area residents over

the next 20 years. But, it doesn’t work without air cargo as a catalyst.

Below is a response to the hypothetical question, “What level

of activity and impact could be ‘purchased’ if the state was

to entirely expend the $300 million1 in state tax credits set aside for

‘qualifying gateway facilities’ in SB390 by the time the program

sunsets?” The ultimate benefit to the state will be weighed

against the total potential cost of $360 million paid out over 15 years,

including the $60 million component for freight forwarders.

China has determined to grow their market share in air freight from 15-20%

to 50% for Chinese-made goods that fly between their country and the U.S.

They have the resources and political will to make this happen. They will

also establish an air cargo “bridge” to link China to Brazil

and the rest of South America by air. It’s not a question of whether

China will do these things; only whether they will do them in St. Louis.

Economic Development Potential of Air Cargo

Three airports in particular, none too distant from St. Louis, show the

power of introducing international air cargo to a passenger airport. All

have the added advantage of being home to one of the two largest expeditors,

UPS or FedEx, but remain great comparisons for illustrative purposes.

• Louisville – “The

expansion of Louisville International Airport has created more than twice

as many local jobs as experts projected when the city embarked on the

project in the late 1980s, according to the latest version of a long-term

economic impact study. The airport now generates more than 55,000 jobs,

according to the University of Louisville study, which is updated every

three years. It also generates nearly $2 billion in payroll and $277 million

in state and local taxes – more than four times the original projection

in those categories, according to the study. Almost all the impact can

be attributed to the UPS Worldport global air hub …”

• Memphis – “A

new study released this week confirmed the airport’s muscle, estimating

that Memphis International pumps $28.6 billion into the region’s

economy and provides, directly or indirectly, 34.2 percent – or

one in three – local jobs. The economic impact study was commissioned

by the Memphis-Shelby County Airport Authority and conducted by the Sparks

Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of Memphis.

Cargo accounted for $27.1 billion of the total economic impact and 208,319

of the 220,000 jobs related to the airport, according to the study.”

• Indianapolis – Although

Indianapolis International Airport is only the 45th largest U.S. airport

in terms of passenger traffic, it is the nation’s 8th largest cargo

facility and 21st in the world due to a major presence by FedEx. Because

of this added revenue from air cargo, and in spite of just completing

a new $1.1 billion midfield passenger terminal, the following is true.

“In most U.S. cities, the rates airlines pay are forecasted to increase.

In Indianapolis, however, those costs will actually decrease steadily

over the next five years, which will make Indianapolis International more

attractive for additional or expanded air service.”

Several additional examples\ of U.S. inland ports offer a glimpse of what

an international freight hub can become over a 10 – 20-year period.

What is very clear from the examples to follow, though each is unique,

is that the investment and job-creating power of effectively combining

air transport with a robust rail and highway infrastructure is incredible.

Add to that the advantage of St. Louis’ location at the confluence

of the nation’s two largest rivers, and China’s entry into

the marketplace -- and the potential multiplies exponentially.

• Rickenbacker / Columbus

Inland Ports - Columbus, Ohio. Rickenbacker is a 5,000-acre all-cargo

airport, which anchors the southern end of a 15,000 acre industrial zone.

It contains over 22 million sf of class “A” distribution and

logistics space that employs over 15,000 workers. The Rickenbacker Port

Authority has developed 10 million sf over the last 10 years in the FTZ

industrial park. An additional 12 million sf have been developed in 12

other industrial parks in the Rickenbacker area over the last five years.

• Port of Huntsville –

Huntsville, Alabama. The Port of Huntsville is an inland port complex

located in Northern Alabama comprised of three facilities: Huntsville

International Airport, the International Intermodal Center, and Jetplex

Industrial Park. A 2008 economic impact study for the Port of Huntsville

summarized its findings as follows, “These employment and payroll

figures are larger than those reported in similar impact studies for the

airports in Birmingham, Nashville and the passenger-only part of the Memphis

Airport.” Note that Huntsville’s metro population is approximately

450,000 – compared to Birmingham at 1.2 million, Nashville at 1.6

million, and Memphis at 1.3 million.

• San Bernardino International

Airport (SBD) – San Bernardino, California. Located 60 miles east

of the Los Angeles International Airport, SBD is surrounded by major interstate

freeways and is within two miles of the BNSF intermodal facility. Alliance

California is a 2,000-acre “trade and logistics” center adjacent

to SBD and operated by the Hillwood Group, who is also the developer of

the Alliance Global Logistics Hub in Ft. Worth, Texas. There are multiple

buildings in existence or under development at Alliance California totaling

roughly 64 million square feet. Hillwood estimates that over 29,000 jobs

have been created at Alliance California since 2000.

• Alliance Global Logistics

Hub – Ft. Worth, Texas. A 17,000-acre, master-planned development

built around Ft. Worth Alliance Airport, the world’s first 100%

industrial airport, with two Class I rail lines, and multiple interstate

highways. Launched in 1989, this development is estimated to have more

than 170 companies and 28,000 employees.

• Port of San Antonio –

San Antonio, Texas. The Port of San Antonio was created out of the closing

of Kelly Air Force Base in the 1995 round of Base Realignment and Closures.

An economic impact study6 performed in 2010 summarized its annual impact

as follows. “The business operations at Port San Antonio generated

an (annual) economic impact of about $4.14 billion. This activity supported

employment of about 24,216 full-time equivalent positions and paid incomes

to these workers of $1.68 billion. The value added is estimated at over

$2.65 billion, and the total fiscal impact was $467 million to the federal,

state and local governments.”

Estimated Impact of SB390 Economic Pro Forma

The assumptions above were provided by the RCGA to Princeton-based Biggins

Lacy Shapiro (BLS) who is working in tandem with the international logistics

advisory firm Institute St. Onge to conceptualize how the introduction

of international air cargo in St. Louis catalyzes the entire multi-modal

transportation cluster and evolves into a legitimate international cargo

gateway. Based on those specific assumptions, BLS / St. Onge’s modeling

suggests the following economic impacts.

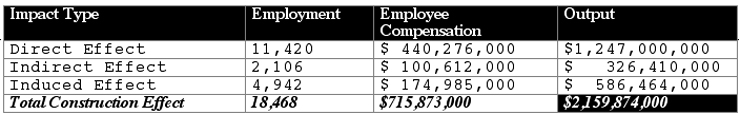

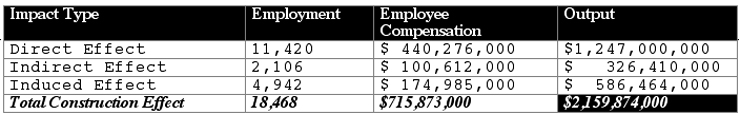

Cumulative Construction Impact: 2011 - 2018

(SB390 requires facilities built within 8 years):

|

. Notes:

. Total construction employment represents the total number of full time

equivalents (FTE) positions created during the project’s eight-year

construction period. This is not the number of people employed. Individual

employees may have more than one job during the multi-year construction

process.

. Output and employee compensation presented in 2011 dollars.

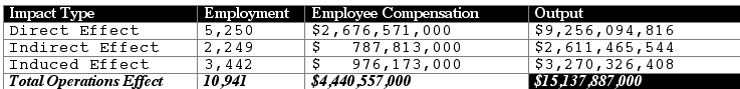

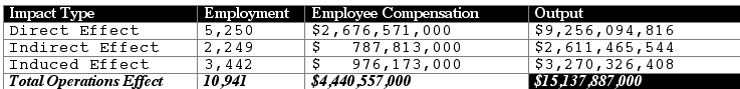

Cumulative Operations (Full Time

Jobs) Impact: 2011 – 2025

(SB390 incentives paid out over 15 years)

|

. Notes:

. Operations jobs represented as full time equivalents (FTE) positions

per year.

. Output and employee compensation presented in 2011 dollars.

Total combined output over 15 years: $17.3 billion. These estimated

impacts are for the 8-county Missouri portion of the St. Louis metropolitan

area and the rest of the state of Missouri.

Using the same methodology, the combined output over 20 years (2011 –

2030) is $26.8 billion.

State Financial Returns

The construction and operations impacts above, along with the Key Assumptions

on page 5 were provided to St. Louis-based Development Strategies to calculate

revenue returned to the state at 15 and 20-year intervals. Based on Development

Strategies’ modeling, the cumulative effect of individual and corporate

income taxes, state sales and use taxes, and all other state taxes would

be approximately $347 million over 15 years and approximately $460 million

over 20 years.

Key Assumptions for SB390 Economic Pro Forma

. $300 million of Aerotropolis incentives, fully subscribed, will generate

$1.25 billion of new construction

. $150 million as 30% credit yields $495 million of new investment

. $150 million as 20% credit yields $750 million of new investment

. $1.25 billion of new construction will be configured as follows

. 15% by value ($187 million) will be dedicated air cargo space built

at $85 psf.

. Generates 2,200,000 sf of air cargo space

. 85% by value ($1.06 billion) will be warehouse space built at $54 psf

. Generates 19,600,000 sf of warehouse space

. Total of 21.8 million sf of new construction

. Average cost of equipping facilities estimated at $15 psf

. Facilities built out over 8-year period at following growth rate:

. 2011 – 5%

. 2012 – 20%

. 2013 – 25%

. 2014 – 30%

. 2015 – 5%

. 2016 – 5%

. 2017 – 5%

. 2018 – 5%

. Employment projections based on densities consistent with St. Louis

warehouse and transportation market, which are more conservative than

densities for manufacturing employment

. Whse: 7,328 sf per employee7

. Transp: 9,587 sf per employee8

. NOTE: You have both in each facility – not exclusively one or

the other

. Total new employment projections based on 8-year build-out of new facilities

and employee densities listed above

. Whse: 2,975 employees (21.8M sf ÷ 7,328 sf per employee)

. Transp: 2,274 employees (12.8M sf ÷ 9,587 sf per employee)

. 5,249 new direct employees over 8 years

. Further employment assumptions for IMPLAN model

. Employment ramps up at same rate as facilities over 8 years

. Payroll then grows at an inflationary factor calculated by IMPLAN for

7 years (years 9 – 15)

. 35% of the jobs are classified as “other miscellaneous manufacturing”

and use the existing IMPLAN data for calculating wages and benefits

. 35% of the jobs are classified as “warehouse and transportation”

and use the existing IMPLAN data for calculating wages and benefits

. 30% of the jobs are classified as “air cargo” and use the

existing IMPLAN data for calculating wages and benefits

Economic Impact Definitions

The economic impact of a business, organization, or event is a measure

of the amount of, and the way that, dollars associated with that entity

circulate through the region. The estimates presented in this summary

were developed with a computer model called IMPLAN, which stores a profile

of the St. Louis MSA economy in a database. The model uses production

functions for each industry in the region to calculate how spending in

one industry circulates through other industries in the St. Louis MSA.

This economic impact can be expressed either as an annual flow of dollars

(output) or an equivalent number of employees.

There are three levels of impact that are considered when developing these

figures: the direct impact, the indirect business spending impact, and

the induced household spending impact. All three can be expressed in terms

of an annual flow of dollars (output) or annual jobs. The total impact

is the sum of these three factors.

. Direct Impact

. This is the most basic part of an organization’s economic impact.

It measures the dollars and jobs that the organization directly generates.

When expressed in dollars, the direct impact is an approximation of a

company’s output. Alternatively, the direct impact is the average

annual value of output associated with the given number of jobs in that

industry.

. Indirect Business Impact

. This is a secondary measure of a business’s economic impact. It

represents the dollars and jobs generated by the operating expenses of

the organization. Examples might be purchase of raw materials from a local

supplier or the professional services of an accounting or law firm. This

spending generates revenue and employment at firms that supply those goods

or services. Every dollar that an organization spends locally to conduct

its business supports another business in some way.

. Induced Household Spending Impact

. This is a tertiary measure of a business’ economic impact. It

is a measure of the business revenue generated by the personal spending

of the organization’s employees. Think of an employee at an organization

spending money at the local grocery store. The employee’s paychecks

support revenue and jobs the same way that the organization’s spending

on equipment supports revenue and jobs.

IMPLAN DEFINITONS

Output represents the value of industry production. For manufacturers

this would be sales plus or minus change in inventory. For service sectors

production = sales. For retail and wholesale trade, output = gross margin

and not gross sales.

|