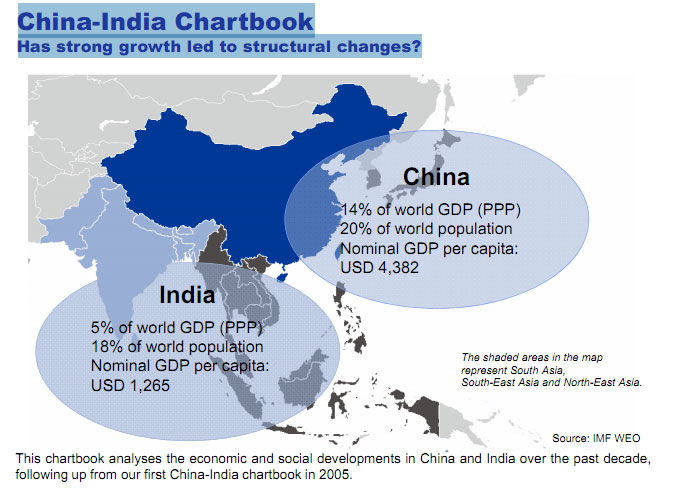

Nearly everybody in transportation

wants a piece of the action that is taking place in China and India

right now.

But what do bankers think?

Here is an update on both of these markets

just released by Deutsche Bank Research.

China and India have experienced robust

growth over the past decade, spurred by different drivers.

Growth has averaged over 10 percent in China and nearly 7.5 percent

in India since 2000. The services sector grew in both China and India

as a share of GDP and this growth mainly came at the expense of the

agriculture sector.

The WTO agreement had a significant impact

on China’s investment, the share of which in GDP growth went from

22 percent in 2000 to over 50 percent by the end of the decade. India’s

growth, on the other hand, has primarily been driven by consumption.

Investment, though increasing, still lags

behind China’s.

Fiscal accounts and inflation have deteriorated

over the past 1-2 years.

Both countries put in place large stimulus

packages during the global financial crisis, which were effective in

preventing a sharp decline in economic growth.

Stimulus has started to be withdrawn,

but nevertheless fiscal accounts remain in worse shape than before the

crisis. This is a concern particularly in India, given high levels of

fiscal deficit and public debt. Despite recent tightening, monetary

policy remains loose, which, together with increases in commodity prices,

has led to strong inflationary pressures in both economies.

Banking sectors remain in good shape,

as conservative regulation has shielded them from the fallout of the

financial crisis. Given the relatively closed nature of domestic financial

markets, the abundance of local savings and stringent regulation on

leverage, China and India did not experience a boom-and-bust cycle in

capital inflows during the global crisis.

Over the medium term, a favorable GDP

growth outlook and low penetration of financial instruments herald bright

prospects for local capital markets.

Living standards for the population have

improved dramatically, less so the environment for business.

The increase in GDP per capita and the reduction in poverty have been

staggering, although income inequality has increased. The business-operating

environment has also improved, but further income inequality has increased.

The business-operating environment has

also improved, but further progress is needed in a number of areas.

Infrastructure and environmental issues have gained prominence and there

is more to come.

Both countries’ 5-year development

plans place substantial emphasis on infrastructure development.

The energy sector (including nuclear energy)

is also developing quickly given increasing domestic demand.

China has made the environmental upgrading

of old coal plants a priority, and the market for renewable energy in

India has been growing at 25 percent per year.

A Tale Of Two Growth Models

China has outpaced India.

China has consistently grown at a faster

rate than India during 2000-2010, resulting in a widening gap in both

nominal and per-capita GDP.

Although investment has been increasing

in both economies over the past decade, it is a significantly stronger

driver of growth in China than in India.

In China, investment began to overtake

consumption’s contribution to growth after the country’s

accession to the WTO in 2001. Given China’s large population and

vast physical size, the investment “takeoff” stage has several

more years to run, moving now from coastal areas to inland provinces.

Both countries are seeking to diversify

the structure of their economies.

In China, investment will remain strong

for several years, but the government is seeking to increase the share

of consumption once again.

In India, ongoing liberalization in foreign

investment restrictions and strong growth prospects should help Gradual

Shift Towards Service Sector

The share of industry in relation to GDP

has remained largely stable in both countries, while the services sector

has grown at the expense of the agricultural sector.

This trend highlights the importance of

improving agricultural productivity to ensure long-term food security

and moderate spikes in food inflation.

Both China and India significantly increased

public spending during the crisis to support growth, and that is only

being withdrawn slowly.

India’s high spending on subsidies

is keeping the deficit at a more concerning level while China’s

deficit has been moderate, partially because of better revenue efficiency

(i.e., revenues have grown at least as fast as GDP).

Expansionary monetary policies have fuelled

inflation.

India’s inflation has been consistently

higher than China’s, but China’s inflation cycle is more

volatile.

Over the past year or so, inflation has

become a serious problem for both countries due to excess liquidity,

upward global commodity price pressures, and high demand for private

property.

Food price inflation is particularly high,

and it risks spilling over into core inflation, and driving up inflation

expectations.

Both countries have witnessed very strong

money supply and credit growth over recent years, causing intermittent

concerns about asset bubbles and excess liquidity.

Population Drives Economic Growth

In both China and India, the population

has grown significantly over the past decade.

But India’s population growth (16

percent) vs. China’s (5 percent) makes it likely that India will

replace China as the world’s most populous country in the next

15 years.

Both China and India benefit from a large

youth population.

The challenge lies in ensuring that the

youth are absorbed into the workforce and that labor force participation

continues to grow. In India, this is a greater challenge given that

its population is even younger than China’s.

By the same token, a younger population

gives India an edge over China with respect to labor force availability

in the future. China’s aging population is going to restrict long-term

growth prospects as the working population is expected to already peak

over the next five years.

Another task for India is to ensure that

female labor force participation (which has remained nearly stagnant

over the past decade) begins to climb.

Doing Business In China And India

Changes in governance have been a mixed

bag over the past decade.

Despite strong growth, governance has

not necessarily improved across-the-board over the past decade.

While government effectiveness and regulatory

quality in China and India are now higher, there have been mixed results

on corruption, security, and contract enforcement.

Moreover, in both economies, political

stability has taken a hit.

Regarding voice and accountability, India

has improved while China has deteriorated, widening the gap between

the two countries, which can be attributed to the nature of their political

systems.

Business environment remains onerous in

India, but there have been significant strides in protecting investors

and creating access to capital.

India remains a notoriously difficult

business environment (ranking 135 out of 185 countries in terms of ease

of doing business), but the country outshines China in some areas; for

example, it does far better in terms of access to financing and protecting

investors.

Nevertheless, further improvement in removing

administrative hurdles is needed not only to attract foreign investment

but also to enable local businesses to thrive.

All things considered, China remains a

more attractive business environment not only compared to India, but

also to Brazil and Russia.

|

Walter

Bachmayr

Walter

Bachmayr