|

The man has kerosene in his blood. His

father was professor for airport construction at the University of Technology,

Berlin, author of the standard textbook “The History of the German

Commercial Airports,” and from 1953 to 1978 Managing Director

of the association of German airports (ADV). His father-in-law was a

training captain with the German Armed Forces; his brother-in-law flew

the Boeing 707 freighter and was a pilot of a 747 for the last eleven

years of his Lufthansa career. When Treibel met his wife, she already

had her glider certification. All this has had an influence on Hans-Peter

Treibel.

The airplanes flying over his house in

the small Taunus town of Hofheim are easy to hear, but for Treibel,

“it’s music to my ears.” His father built the house

directly in the Frankfurt airport approach path and his son could recognize

every airplane by its engine noise. It is almost superfluous to mention

that Treibel has spent his professional life in aviation: 37 years with

Lufthansa, 37 years with Cargo.

Treibel is 70-years old and the "father"

of the Lufthansa Cargo Centre (LCC) in Frankfurt. Many Lufthansa Cargo

terminals—in New York, Dallas, Los Angeles, London or Shanghai—have

been designed and built by him.

Treibel was born in 1941 in Vienna. His father,

Dr. Ing. Werner Treibel, worked there for Lufthansa and thus Hans-Peter

grew up with aviation. After the war, father Treibel forged the plans

for the resurrection of the “crane” with Hans M. Bongers,

who became the Chairman of the Executive Board after the re-founding

of Lufthansa in 1954.

The Treibel house was often frequented

by Ludwig Bölkow, later the Managing Director of the Messerschmidt-Bölkow-Blohm

GmbH, Ernst Heinkel, builder of the first jet-propelled airplane—the

Heinkel He 178—as well as Wolf Hirth, glider pioneer and Eugene

Sänger, pioneer of aviation and space travel, who developed the

concept of the orbital glider – the Space Shuttle.

Often, the young Treible filius was allowed

to be present when the luminaries in the world of aviation told their

stories of the past and speculated as to what the future held in store.

At the age of 14, the young man founded his own Airline—on paper—and

at 19 he completed his final exam (Abitur). Upon completion, he immediately

began an apprenticeship with Lufthansa Technik in Hamburg and then began

his mechanical engineering studies in Stuttgart.

Regarding the apprenticeship in the Lufthansa

Maintenance hangers in Hamburg, he muses in retrospect, “apparently

I must have left a good impression.” When he applied three years

later with Lufthansa for a foreign apprenticeship with Boeing in Seattle,

where a small but feared troop of Lufthansa engineers oversaw the construction

of the aircraft ordered by the crane, he was approved as the first student

to ever qualify for such an apprenticeship. It was the first time during

those four months that Hans-Peter Treibel had worn a badge with the

word "Lufthansa" printed on it, and he was very proud of it.

Another apprenticeship with the New York

Port Authority, which was responsible for some of the bridges as well

as for developing the construction plans of the Twin Towers of the World

Trade Center, left a lasting impression on the young and ambitious man.

With a university diploma in hand, in

1969 Treibel applied to the department of Lufthansa’s ground services

in Frankfurt and was taken without hesitation by Karl-Albert "Charly"

Reitz as a project engineer. He didn’t have a lot of time to work

his way into his new position as one new project after another was thrown

at him.

A landmark project was the development

and planning of the Cargo Court No. 3 in Frankfurt with a freight sorting

system, which needed to be bigger and more efficient than all comparable

systems. In addition to engineering services, he was asked for a thorough

assessment concerning the evolution of future freight traffic:. How

will Lufthansa develop; is the volume of freight expected to grow larger;

how large will the packages be; what volume of freight can be expected

in the future; how quickly must the freight be sorted; how many airplanes

will arrive at the same time; how large will the airplanes be in the

future; how will the volume of freight carried by passenger aircraft

develop; do "freight only" aircraft have a future?

It was a truly mammoth assignment, one

which the young engineer had never been confronted with ever before.

As it turned out, these assessments would be the basis of the concept

for a new, huge Lufthansa Cargo Center in Frankfurt, which some time

later would replace the Cargo Court 3.

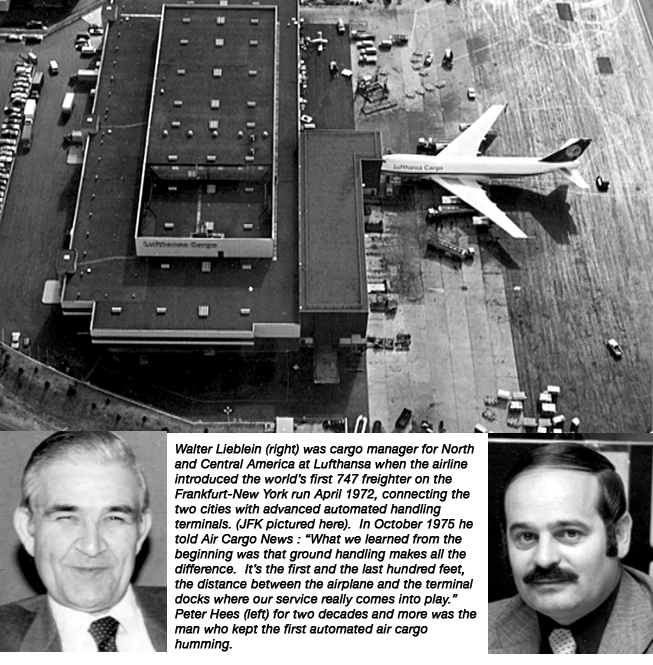

It was the time of the big boom in air

freight. “We had growth rates of ten, twelve percent and more

in a year,“ says Treibel. Lufthansa served the longer distances

with its 707 freighter fleet, and at night the crane operated a freighter

network which was unique in Europe.

17 European flights between Frankfurt and the

most important European destinations like Amsterdam, Barcelona, London,

Milan, Manchester, Paris, Stockholm and Vienna, mostly operated by 727-passenger

planes that were temporarily modified at the airport of destination.

Within an hour, the seats were removed and a passenger plane became

a cargo machine. It flew cargo to the Frankfurt hub, was quickly unloaded

after midnight at “Rhein Main” and was loaded once again

with cargo which had arrived from overseas or from European airports

on the same evening. This cargo was then flown overnight, reaching its

destination—for example, Stockholm—at the crack of dawn.

There, the airplane was re-equipped with seats once again. About 7:00am,

it took-off with passengers on board returning to Frankfurt. “The

Quick-Change System was unique in Europe“, tells Hans-Peter Treibel,

“Lufthansa was praised for it in all the trade journals as the

most advanced airline in the world.“

Success has its price. When the Cargo

Court 3 with its freight sorting system went into operation in 1973,

it quickly was rendered too small. No wonder that Hans-Peter Treibel

(who had in the meantime advanced to be head of the Freight Systems

department), together with his team of young, visionary engineers, had

long since put their heads together on a much bigger project. In a one-to-one

discussion with Hans Süssenguth of the Lufthansa Executive Board,

Treibel demonstrated that in a cargo hub like in Frankfurt, with more

than 70 percent transit cargo, time on the ground and expenses could

only be adequately controlled with extensive automation of the cargo

handling. Besides that, available space in Frankfurt was becoming scarce

for warehouses with rolling bins and freight sorting systems. The boss’

answer: “plan how the freight handling will look, and then we’ll

talk further.”

Treibel and his team went to work. Their

maxim: Optimize the processes on the ground, so as not to frivolously

lose the aircraft’s time advantage again. There were only a few

reference programs worldwide and unfortunately they were designed substantially

smaller, too compactly and too minimally adaptable with regard to changing

developments in the cargo’s features and its ability to be put

into containers. The team did not want to make the same mistakes. The

biggest cargo terminal in the world that was being planned for Frankfurt

should consist of extendable modules, which, without interrupting the

normal operations, could be enlarged later without interfering with

the technology and basic architecture. The Lufthansa Executive Board

later stated the assignment more precisely: The cargo terminal must

also fulfill the capacity requirements for the year 2000, it must master

the most modern warehousing, conveyor technology and process control

and may not cost more than 250 to 300 million DM.

That was almost like squaring off the

circle, particularly because in the areas of IT, many new approaches

would have to be taken. An example of this was the contractual modalities

with the airport operator FRAPORT, which did not sell their property,

but rather ceded it to Lufthansa through a rental and building contract

over a 30-year period.

Within this time frame the entire area

had to be developed, including the laying of pipelines, building rainwater

retention basins, and building sewers to the Main River, as well as

the construction of a noise barrier wall. The cost evaluation, profitability

calculations and contracts were all new territory. The grounds, which

at that time were in the middle of a forest and former ammunition dump

from the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, brought a few surprises.

“The project was sheer pioneer work,” Treibel recollects

looking back, and thus explains why it took eight years from the planning

phase to the completion.

When the Lufthansa Cargo Center finally

started operations in June 1992, it was indeed the largest and the most

modern airfreight terminal in the entire world. It was so high tech

that the personnel were confronted daily with completely new warehouse

logistics, and the operation took the better part of a year before it

was gradually up and running. Treibel is proud that after almost 30

years of operation his “baby” still runs at peak power 24

hours a day, 365 days a year.

|

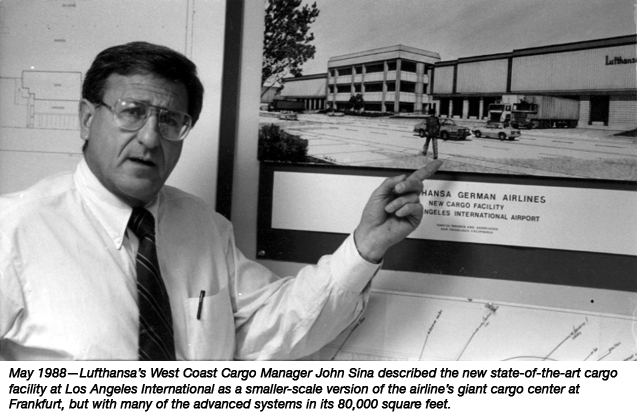

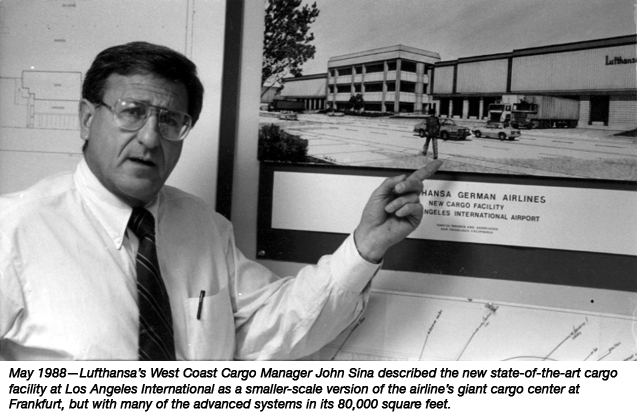

In recognition of the project work,

Hans-Peter Treibel was named Director of “Cargo Handling Processes

and Freight Facilities” (two years before the opening of the LCC!)

for all Lufthansa stations worldwide. Treibel planned and built freight

terminals for Lufthansa in New York, Los Angeles, Dallas, London and

Shanghai and became more and more an “all around” expert.

Planning was the one side. Contract negotiations and completions required

commercial management, legal expertise and the sensitivity to deal with

various cultures and mentalities in order to select the right person

for an assignment.

Treibel continued climbing the ladder

of success and was appointed Manager in Charge of Sales- and Service-Systems

Cargo and from 1991 until 1996 he was General Manager of TRAXON, a joint

venture company of Lufthansa Cargo, Air France, Cathay Pacific, Japan

Airlines and Korean Airlines.

Back with Lufthansa, a great number of

large projects were on his to do list. He was involved in evaluating

and finding a location for the DHL Express-hub in Brussels and was,

for the most part, involved in the planning of Leipzig’s new hub.

After extremely tough negotiations with

the Chinese partners, the freight center at Shanghai’s Pudong

Airport wasin the bag and even “on time and on budget,”

Treibel once again had left his footprint on a major project.

From 2000 onwards, Treibel returned to

his home base and to the heartland of the company. The Executive Board

entrusted him with overseeing the interests of Cargo with the upcoming

expansion of the Frankfurt Airport. In plain language: Treibel was expected

to make sure that Lufthansa Cargo would continue to expand and he was

to do everything possible to try to ward off the threatened ban on night-flights.

Unfortunately, this assignment was not

to be fully realized. After 37 years of service to Lufthansa, he retired

in 2006 when he turned 65. For him, it was a sort of “forced retirement,

because I would have been content to remain in the job”. The kerosene

in his veins still pulses with the same intensity.

Five years later, Hans-Peter Treibel

is convinced that “the courts will not be able to stop the expansion

of the Frankfurt Airport and a night-flight ban won’t go into

effect.”

Note: Germany will go gala over air cargo with a week long celebration

that commences on August 17th and begins with the unveiling of a new

book commissioned by Lufthansa entitled “100 Years of Air Cargo.”

The landing page to keep up with the latest happenings and celebration

of 100 Years of Air Cargo is http://www.100-years-air-cargo.com/

|

![]() 100%

Green

100%

Green